The Strategic Theory of John Boyd

If you are interested in strategy, you will likely encounter military strategy. If you get interested in military strategy, you will likely encounter a man called John Boyd.

To some people, Boyd was one of the greatest military strategists of all time, alongside Sun Tzu and Karl von Clausewitz.

To others, he was a crackpot. Cedric Chin quotes USAF Chief of Staff General Merrill McPeak, who said: “Boyd is highly overrated…in many respects he was a failed officer and even a failed human being.”

I don’t endorse joining the military, but I do endorse learning about John Boyd. Over the last three years, I’ve read many books about Boyd and his ideas. In this post, I will synthesize my own research and understanding of Boyd’s account of strategy in general, not specifically with respect to military applications but as applicable in business, non-profit organizations, and my own personal domain of interest, monasteries.

Who was John Boyd?

Over the course of his career, Boyd went from being one of the best pilots and dogfighters in the US Air Force, to providing the theoretical foundation for the military reform movement in the 1970’s and 1980’s.

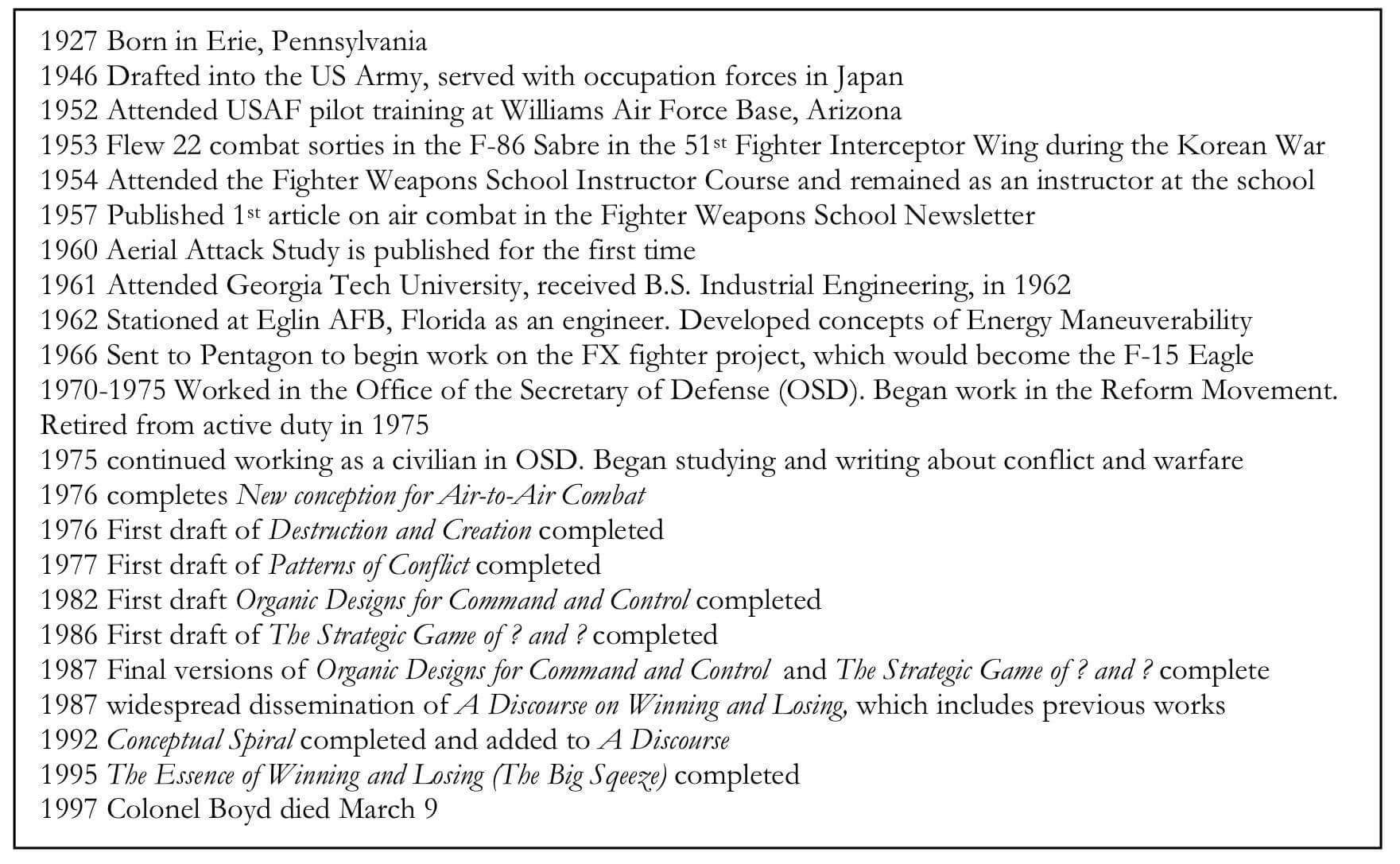

Biographical History of John Boyd’s life – Osinga’s Science, Strategy, and War (p. 41)

John Boyd’s formal military career began in 1944, when he enlisted in the US Army.

In the early fifties, he transferred to the US Air Force, where he became a star pilot during the Korean War, and later became an instructor at the prestigious Fighter Weapons School.

There, he found a passion for teaching and sharing his insights, which culminated in the publication of his famous Aerial Attack Study, which Ian T. Brown says “was such a thorough piece of work that no significant contributions have been made to fighter tactics since its publication.”

In the early sixties, he received a degree in Industrial Engineering from Georgia Tech University. He combined his newfound skills in mathematics and engineering with his intuition for aviation to create Energy-Maneuverability (E-M) Theory, which allowed engineers to determine an aircraft’s performance characteristics or to design an aircraft to optimize performance.

E-M Theory allowed Boyd to compare the relative performance of American and Soviet planes, leading to the astonishing realization that Soviet aircraft tended to perform better than the American planes. This shock enabled the United States military to course correct, and to develop new aircraft that exceeded Soviet weaponry. Boyd used his E-M theory in these efforts, leading to the creation of multiple aircraft, including the F-16 Fighting Falcon, as well as the F-15 Eagle, The F/A-18 Hornet, and the A-10 Thunderbolt II.

After his official retirement in 1975, he continued to work, but as a civilian. This final phase of his career began with a period of research. Boyd intensively studied topics like science and history in order to work towards a more general account of conflict, strategy, and victory.

Boyd’s research gave him a theoretical basis for adapting his insights in domains like aircraft combat and design to war and conflict more broadly. He fleshed these theories out in a series of presentations that he developed from 1976 to 1995: Destruction and Creation, Patterns of Conflict, Organic Design for Command and Control, The Strategic Game of ? and ?, Revelation, and The Essence of Winning and Losing. Boyd delivered these presentations repeatedly to audiences in the Pentagon and different branches of the military. These presentations were known for taking hours, or in some cases, days.

Boyd’s research, theories, and presentations formed a significant component of the military reform movement in the 1970’s and 1980’s. These presentations also led to the development of the philosophy of maneuver warfare, as adopted by the Marine Corps and some other branches of the military.

In 1990, he was also asked by Dick Cheney, as George H. W. Bush’s Secretary of Defense, to help develop a strategy for Operation Desert Storm, the first Gulf War. The first Gulf War’s rapid speed—42 days in early 1991—has been attributed to Boyd’s influence.

Boyd was a practitioner, a researcher, a theoretician, and a pragmatist. He based his theories on both his first-hand experience and his research, and used his theories to enact change in multiple branches of the U.S. military, in multiple different ways throughout his official career and even after his formal retirement.

What were Boyd’s major ideas?

Although Boyd was primarily interested in military strategy, his ideas illuminate strategy and conflict more broadly. He offered what Frans Osinga calls a “comprehensive theory of conflict,” including the levels of tactics, operations, strategy, and grand strategy.

Some have seen him as a “great synthesizer,” integrating a wide range of ideas from military history and contemporary science into a contemporary account of strategy. Osinga claims this view is incomplete, as “it fails to acknowledge genuine novel elements he added to this synthesis” and the ways in which his ideas transcend “those of classical theorists of the manueverists school of strategic thought.”

For example, it would be easy to limit Boyd’s work to merely re-hashing Sun Tzu’s ideas for the 20th century. Indeed, Osinga claims that Sun Tzu “must be considered the true conceptual albeit ancient father of Boyd’s work.” Boyd repeatedly read Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, and it was “the only theoretical book on war that Boyd did not find fundamentally flawed.”

Osinga believes that while Boyd was heavily inspired by Sun Tzu, Boyd also made novel contributions to Sun Tzu’s work “by rediscovering, translating and updating the concepts of Sun Tzu and the other strategists to suit the era he found himself in. To Sun Tzu Boyd adds the Blitzkrieg concept which re-combines, according to Boyd, the elements that have historically produced success using the new tools of this century; the tank, the aircraft and modern communication equipment. To some extent one could also consider his rediscovery of operational art a novelty in his day.”

Osinga sees Boyd as “the first postmodern strategist both in content and in his approach to making strategy and strategic theory.” He demonstrates that through his reading, Boyd was familiar with the questions and research in the larger scientific and epistemic Zeitgeist, and worked to develop an account of strategy that was consistent with these findings.

Unfortunately, learning about Boyd’s ideas is challenging and laborious, for several reasons. Most importantly, Boyd never wrote a treatise summarizing his thoughts and works as a whole. Destruction and Creation is an essay, but it is a brief eight page document. Boyd’s basic approach to research and sharing his ideas was creating, delivering, and refining oral presentations. While some recordings of Boyd exist, these presentations are largely preserved in the form of slides, which are difficult to understand without Boyd’s verbal explanations or the analysis of experts like Osinga. Moreover, the slides exist in different versions, as Boyd iterated on his presentations over time as his thinking evolved.

Another challenge in learning Boyd’s ideas is that not all of his adherents understood his ideas completely. Brown in particular criticizes William S. Lind, who promoted Boyd’s ideas widely but had an “incomplete interpretation” that “reached a much wider audience, but…left the nuances of Boyd’s briefings behind.” This has resulted in oversimplifications of Boyd’s ideas, which can look trite and underwhelming in their watered down forms.

In what follows, I will present and summarize the most important ideas I’ve come across from Boyd. I will present them in the most general form possible, without overly emphasizing their military applications.

Uncertainty

Boyd’s account of strategy claims that uncertainty and change being a fundamental aspect of conflict and, more generally, life itself. Rather than avoiding uncertainty, embracing it will help individuals and organizations to survive and thrive.

Boyd’s emphasis on uncertainty comes from a variety of sources, but most notably it comes from his unique connection between and synthesis of Gödel’s incompleteness theorem (“One cannot determine the consistency of a system within itself”), Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle (“One cannot simultaneously fix or determine precisely the momentum and position of a particle”), and the Second Law of Thermodynamics (“All natural processes generate entropy”). Boyd claims that “taken together… [these proofs] say that one cannot determine the character or nature of a system within itself. Moreover, attempts to do so lead to confusion and disorder.”

OODA

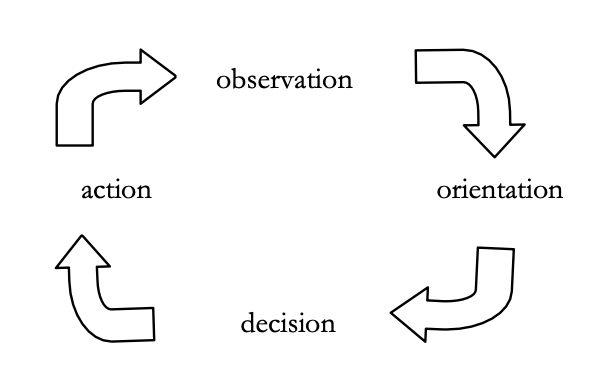

Boyd’s most famous idea is his “OODA loop,” also known as the “decision cycle” or “Boyd cycle.” Typically, this is presented as a four-step process that relates to decisions or conflicts at any level:

- Observation: noticing or perceiving a situation (“I see a fast object coming towards me!”)

- Orientation: interpreting or making an estimation of the situation (“That’s probably a drunk driver! They might hit me!”)

- Decision: making a decision of what to do about that situation (“I’m going to jump out of the way.”)

- Action: taking the action (Jumping out of the way)

This action creates a new situation, and the loop can repeat itself.

Simplified OODA Loop – Osinga’s Science, Strategy, and War (p. 2)

Each person or group operates within their own decision cycle. The person who loops through the OODA loop faster has an advantage over their enemies. There are two ways to be faster: to move faster, or to cause the enemy to be slower by creating friction. Either way, you loop faster and more effectively than your enemy, you will succeed. Seen through the lens of the OODA loop, time is a major advantage if used well.

While this way of understanding of the OODA loop can be useful, it is an oversimplification. This oversimplification is useful at the tactical level but less so at higher levels of strategy. It also leads to an overemphasis on speed. Brown says that Boyd criticized maneuverists who “clung to the idea of absolute speed, [responding] ‘Christ, we’ll all drive each other nuts.’” The main point for Boyd was to have relative speed: “All I have to do is be faster than my adversary. I can be slow as long as I slow [him] down even more.” To take the OODA loop at face level would be to miss its deeper significance, which has applications at all levels of strategy.

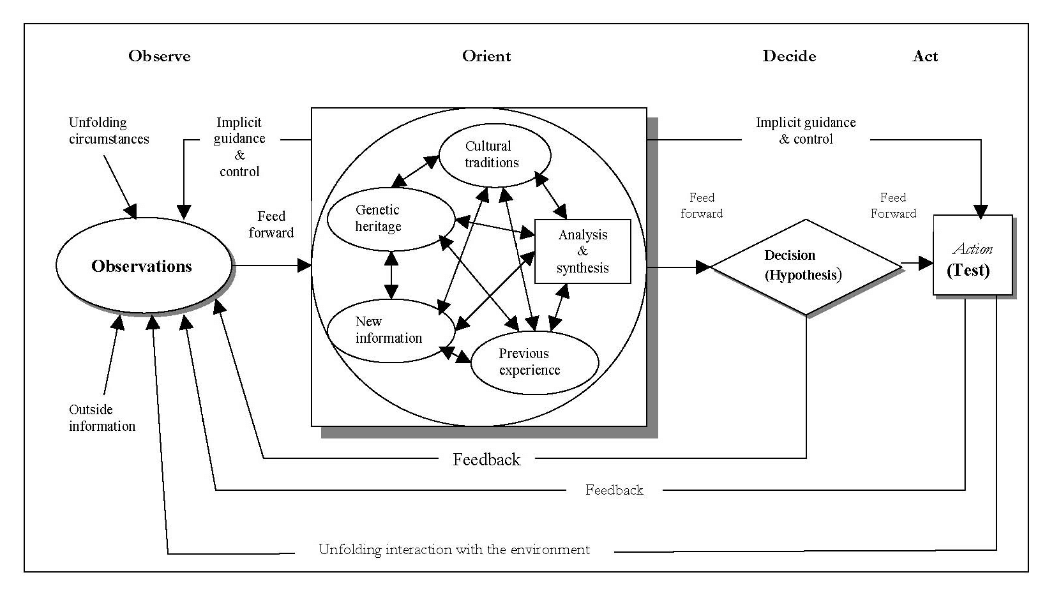

Towards the end of his life, Boyd created a more complete rendering of the OODA loop. Here is the full OODA loop:

The Real OODA Loop – Osinga’s Science, Strategy, and War (p. 270)

Rather than a simple linear loop, each part of the OODA loop has a number of connections with the others. This is what Boyd described as an “ongoing many-sided implicit cross-referencing process of projection, correlation, and rejection.”

In this diagram, Orientation, or the “Big O,” plays a central role: it “shapes observation, shapes decision, shapes action, and in turn is shaped by the feedback and other phenomena coming into our sensing or observing window.”

Osinga explains: “The mental images we construct are shaped by our personal experience, genetic heritage, and cultural traditions, but they are also measured up against incoming new information to validate existing schemata. The entire OODA loop is a double-loop learning process, but the Orientation element itself thus also contains such a double loop feature.”

If we can refine and improve our orientations—our models for interpreting what we are observing—then we will act more effectively than our enemies, or adapt to changing circumstances with more success.

Asymmetric Fast Transients

Much of Boyd’s theories came from his direct experience flying F-86’s in combat and as an instructor. Boyd was famous for a standing bet he developed as an instructor at the Fighter Weapons School. He claimed that if another fighter pilot was on his six (behind him), he could reverse their positions within forty seconds. If he failed, he would pay the other pilot forty dollars.

As Coram tells it, no one ever beat Boyd, who earned the nickname “Forty-Second Boyd” and may very well be the best pilot in the history of the U.S. Air Force.

Boyd relied heavily on a “quick and violent maneuver” he developed to solve a problem with the F-100 planes, the “adverse yaw problem.” This allowed him to quickly switch positions with another pilot on his tail, so that Boyd would be in the clear defensively and also able to “hose” or destroy his opponent.

Boyd later generalized this phenomenon from air combat in particular to strategy in general with the term “asymmetric fast transient,” which Richards elucidates as follows:

A “transient” is a shift from one state to another, “fast” refers to the time it takes to make the shift (not, as is often thought, the velocity of the aircraft itself), and “asymmetric” means that one side is better at it than the other… fast transients can be found in most any form of competition.

An asymmetric fast transient, like Boyd’s maneuvering of the F-100, is an astonishing and unexpected move to the unsuspecting opponent. It exemplifies excellent usage of the OODA loop concept, where one opponent can operate inside of the other’s OODA loop, with a faster rhythm than their opponent.

The Expected and the Unexpected

This phrase comes from the Chinese words cheng and ch’i. These words are sometimes translated as the expected and unexpected, or as the orthodox and unorthodox. Osinga also translates them as direct and indirect, regular and irregular, extraordinary and normal. Both Sun Tzu and Boyd emphasized cheng and ch’i, the expected and the unexpected, as critical maneuvers.

This concept is straightforward to understand. An enemy would likely expect you to fight them with weapons, but they might not expect you to poison their water supply. Or, for an example from business, Teslas have standard car features like chairs, but also include ‘bioweapon defense mode’ buttons. Chairs are expected. Biohazard modes are unexpected.

Success in any competitive domain requires a combination of expected and unexpected maneuvers. Tesla wouldn’t succeed if they skipped the chairs, or seatbelts. But including features like biohazard modes or a front-facing trunk or any of their other unexpected, unusual features means customers will be drawn to their product, and competitors will be caught off guard.

In the military domain, using a combination of the expected and the unexpected means that you can surprise your enemy, and achieve rapid victory while avoiding unnecessary harm through prolonged engagement.

Induction and Deduction

One aspect of the Orientation part of Boyd’s OODA loop is analysis and synthesis. This relates to deduction, or going from the general to the specific, and induction, or going from the specific to the general. By analyzing and synthesizing our observations and interpretations, we can generate new orientations towards what we are perceiving, so that we can act more effectively.

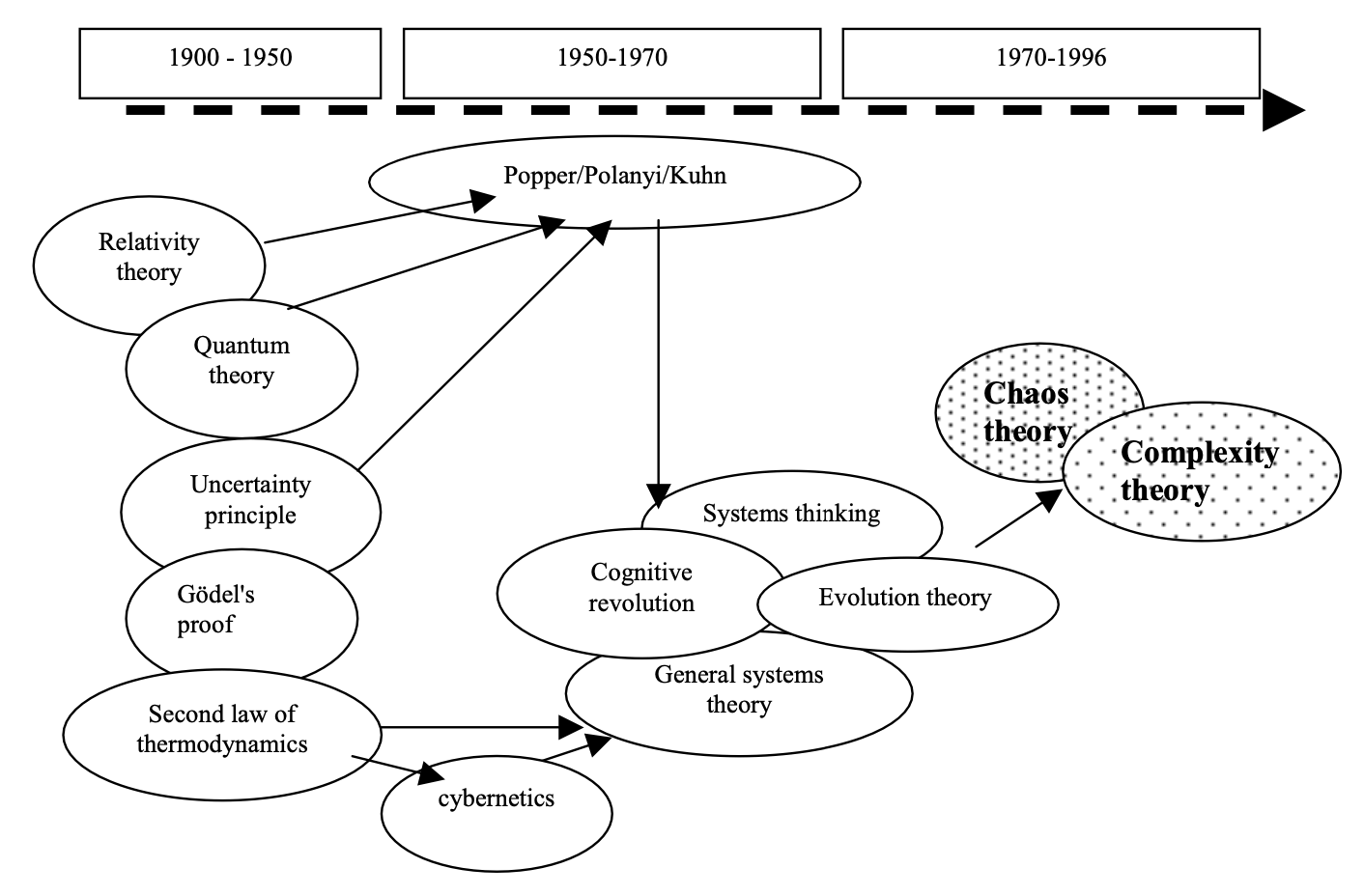

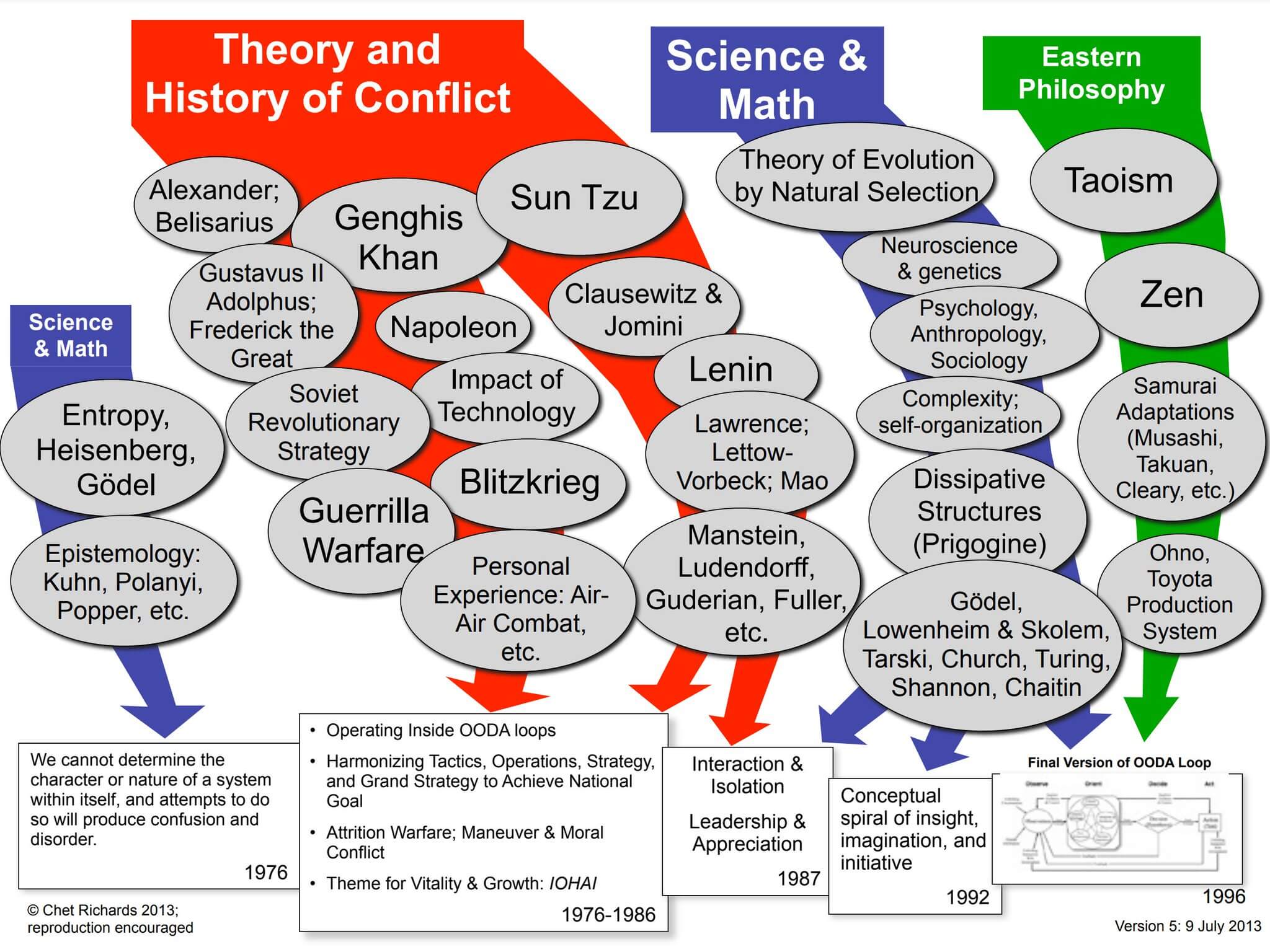

Boyd’s work demonstrated his mastery of analysis and synthesis. His work drew on a variety of influences, adapting them into a coherent synthetic account of strategy writ large. Osinga lists these influences in the following chronological diagram (p. 121):

Chet Richards has a similar diagram listing Boyd’s influences that is also helpful for seeing how they impacted Boyd’s thinking:

Complex Adaptive Systems

Each level of war can be interpreted through the lens of the OODA loop. Each individual, group, and nation has its own OODA loop or OODA loops, which are interacting with each other and evolving over time.

Boyd’s theory fits neatly with the development of complex adaptive systems, an idea which Boyd followed closely. According to Osinga, Boyd would interchangeably refer to armed forces as complex adaptive systems, organisms, systems, processes of transformations, and even brains.

Individuals or organizations that can understand themselves as complex adaptive systems are at a competitive advantage against those that do not.

Moral Warfare

Another important aspect of Boyd’s account of strategy is his emphasis on moral warfare. Like many of his ideas, this accords with his interest in and interpretation of Sun Tzu, the classical Chinese strategist.

Here, the moral doesn’t strictly mean the ethical sense, right and wrong. Boyd defined it in The Strategic Game of ? and ? as “the cultural codes of conduct or standards of behavior that constrain, as well as sustain and focus, our emotional/intellectual responses.”

To put it simply, the moral aspect of war or conflict can be described in terms of trust. If we are teammates or allies, can we trust each other? Do our enemies trust each other? Trust leads to effective collaboration and coordination; mistrust leads to failure. Therefore, the side with more shared trust will succeed.

The moral dimension of war can be weaponized. We can preserve the trust we have internally, while working to sow distrust amongst our enemies. One of the main ways this works is to point out the enemy’s hypocrisy, especially to their followers or citizens. Conversely, preserving one’s own integrity is a way to protect shared trust and therefore effectiveness.

Putting People First with Mission Command

One of Boyd’s famous quips was “People, ideas, hardware—in that order.” Boyd vehemently argued that “Machines don’t fight wars. Terrain doesn’t fight wars. Humans fight wars. You must get into the minds of humans. That’s where the battles are won.”

Because people are more important than ideas or hardware (including firepower, manpower, sheer quantitative superiority, etc.), one must understand psychology, leadership, and management.

From this perspective, micromanagement is poisonous. As Boyd said, “the more you try to control people, the less control you get.”

When we micromanage people, we are implicitly saying, “I don’t trust you.” While it might work in the short-term, micromanagement sows mutual distrust and the conditions for failure in the long-term.

Instead, our leadership style must be built on shared trust and understanding. This trust and understanding takes time to build, and can’t be built on the battlefield or at moments of crisis. Instead, it has to be earned through training and collaboration over time.

Boyd advocated for a leadership style from the Blitzkrieg style of warfare, the German Command and Control system. This form of leadership is often described in contemporary strategy as Mission Command.

In Mission Command, there is a superior and a subordinate. The specific setting doesn’t matter: it might be in the military, or a business, or some other setting. In any case, the superior and subordinate have a mutual relationship of shared trust and understanding, built over years of collaboration.

When a situation arises, the superior has a conversation with the subordinate. They present the situation as they understand it. They then propose a course of action to the subordinate, along with specific notes about requirements or constraints.

Having heard the situation and proposal, the subordinate has two choices. They can accept the mission outright. In this case, they have permission to accomplish the mission in whatever way seems best to them, provided they meet the requirements or constraints mentioned by their superior. They also have permission to adapt to the real-world circumstances that they find.

Their second option is to reject the mission as proposed by the commander, and make a counter-proposal. The subordinate may have reservations about the commander’s interpretation of the situation, or about their specific proposal.

It is their duty to provide their honest opinion about the situation, even if they disagree with their commander. Mission Command won’t work if the subordinate feels uncomfortable sharing their perspective. This is necessary for coming to a shared decision about what to do, at which point the subordinate’s support is expected.

One of the advantages of Mission Command is that it allows the subordinate to adapt the plan, which can be useful if new information arises or communication between the superior and the subordinate becomes impossible. The subordinate is actually on the front lines of a situation, and can combine the latest information with their understanding of the original intent or mission. This enables decentralized decision-making, which can be faster and more effective.

The adaptive and decentralized qualities of Mission Command depends on shared trust. This shared trust is a result of an emphasis on implicit over explicit communication. People and teams that know each other can communicate implicitly and efficiently, and when they are unable to communicate they can anticipate each other’s thoughts or responses to novel circumstances. This familiarity and trust is a result of training and exposure over time, and results in a fast, effective communication style.

FMFM-1 Warfighting gives specific suggestions about how to cultivate this trust over time:

- “First, we should establish long-term working relationships to develop the necessary familiarity and trust.

- Second, key people – ‘actuals’ – should talk directly to one another when possible, rather than through communicators or messengers.

- Third, we should communicate orally when possible, because we communicate also in how we talk; our inflections and tone of voice.

- And fourth, we should communicate in person when possible, because we also communicate through our gestures and bearing.”

Brown adds that these implicit shared knowledge can be trained “by giving [people] constant and repeated hands-on experience under a variety of conditions to build a repertoire of responses and, just as importantly, inculcate decision making and action as a habit.” This has to be developed during peacetime, so disjointed action in war can “all [aim] toward the common end state desired by the overall commander.”

I have described Mission Command and the German Command and Control System from the Blitzkrieg style of warfare in plain English language that will be understandable and useful even outside of the military context. But for those of you that choose to dive deeper into these ideas, it may be useful to note the German words for each of the concepts we have covered:

- Einheit: Mutual trust, unity, and cohesion

- Auftragstaktik: Mission, generally considered as a contract between superior and subordinate

- Schwerpunkt: Any concept that provides focus and direction to the operation

- Nebenpunkt: Secondary points that support the Schwerpunkt or main focus

- Fingerspitzengefühl: Intuitive feel, especially for complex and potentially chaotic situations

Fingerspitzengefühl covers the implicit or intuitive sense for how a novel circumstance should be approached with the intent or mission. While this is usually discussed in terms of an individual subordinate having fingerspitzengefühl for what they should do in a given situation,

Boyd also claimed that it is also desirable for there to be “organizational fingerspitzengefühl…you really want to operate like a family, and you’re a very large family… the whole family’s got the fingerspitzengefühl.”